The proposed 13th Amendment to Belize’s Constitution has sparked a heated national debate, with some critics accusing the government of using crime as a smokescreen to erode civil rights and consolidate unchecked power. In May of this year, Prime Minister John Briceño’s government introduced the 13th Amendment, which aims to change the country’s approach to crime and civil liberties. The amendment seeks to grant the government the authority to declare “special areas” where heightened security measures, such as warrantless searches and arrests, can be implemented. Additionally, it proposes the establishment of a specialized Gun and Gang Court and retroactively validates all previous states of emergency and related government actions enacted since 2018, including those that had previously been ruled unconstitutional by Belizean courts.

Prime Minister Briceño has emphasized and supported the urgency of the proposal, stating, “Crime evokes strong emotions from the citizens of a country… They all deserve strong and decisive action from their government… The state of uncertainty cannot persist for such a long period. So, this is why I am here introducing this, the Belize Constitution, the Thirteenth Amendment Bill 2025, because legislative intervention is necessary.”

Supporters argue that the amendment provides law enforcement with “tougher crime-fighting tools” in response to chronic gang violence, particularly in vulnerable communities. It also aims to clarify the legal authority for emergency declarations, following conflicting court rulings. Minister of Home Affairs Honorable Kareem Musa commented on July 22nd, “There are more safeguards now in this 13th Amendment with the declaration of special areas than there are safeguards for the… Crime Control and Criminal Justice Act.” Notably, the amendment shifts emergency declaration authority from ministers to the Governor General, acting on formal advice.

However, the proposal has drawn intense criticism from activists, legal experts, and opposition members. Critics warn that embedding such powers in the Constitution threatens fundamental rights and could enable long-term government overreach. On July 17th, civil rights attorney Audrey Matura stated,

“We must fight this law! This amendment goes contrary to the current Constitutional Committee which should have canvassed this with the people; but instead, it’s being done underhandedly. Further, given the state of the imbalance of power, as this PUP (People’s United Party) administration has no opposition, more than ever, it should be better canvassed, and people need to understand the severity of implications.”

Opposition Senator Sheena Pitts added, “All they’re doing is putting a pause on what they feel would be a crime-ridden area for one month, limit people’s movements and their freedom.”

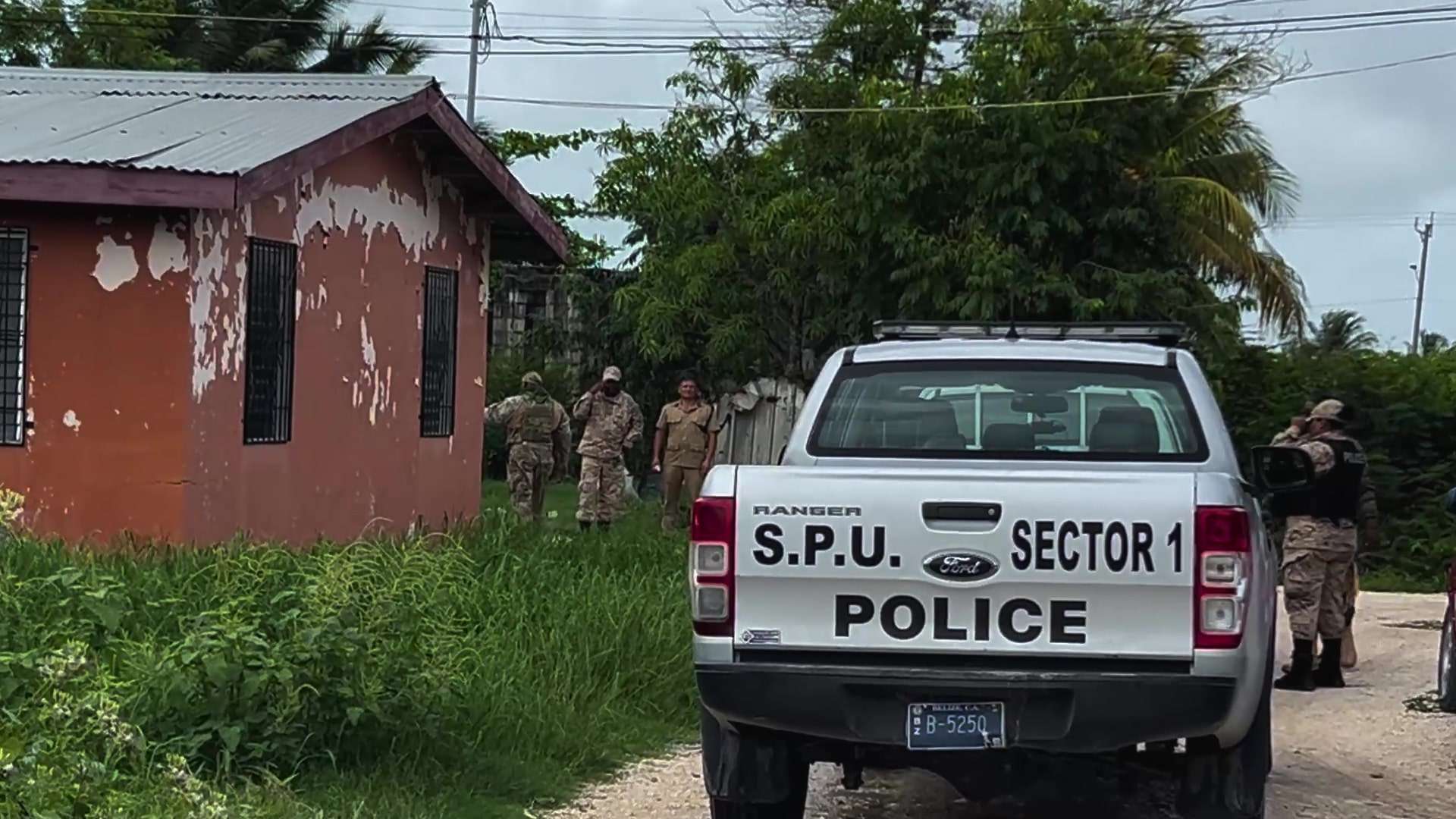

Concerns over rights violations have intensified following a recent incident in San Pedro, where uniformed individuals reportedly conducted a warrantless search at a local business. According to the business operator, three armed men in camouflage entered the premises without prior notice, demanding to speak with the owner and insisting on searching for firearms based on an unverified tip. When questioned about a warrant, one reportedly responded that none was needed and issued a veiled threat of collective punishment if cooperation was not given.

Despite no weapons being found and the situation eventually de-escalating, the encounter left staff and patrons shaken. The incident has fueled growing fears that expanded security powers, such as those proposed in the 13th Amendment, may lead to further abuses under the guise of crime control.

This is one of several reports where police conducted searches outside proper protocols. Business owners worry that if the 13th Amendment is passed, such incidents may become more frequent.

Activists also caution that the amendment’s retroactive validation of states of emergency could legitimize past abuses. “The SOE resorts to fear for control, but such repression leads to resentment, which would lead to retaliation and more violence,” warned Marla Megaña-Cansino of the Belize Network of NGOs.

These concerns have echoed at recent public consultations, with citizens demanding accountability through questions like “Who will police the police?” and calls for “Rehabilitation, not incarceration.”

As Belize weighs the implications of the 13th Amendment, the nation stands at a crossroads, torn between the urgent need for public safety and the steadfast defense of constitutional rights. The debate continues in town halls, government chambers, and across the streets of Belize.

Share

Read more