The Government of Belize (GOB) has set the record straight about its proposed draft Toledo Maya customary land tenure policy, for which it is holding public consultations with all 41 Maya villages of the Toledo district with a review of the policy that is to become law by 2025.

At a media briefing at the Best Western Biltmore Plaza Hotel on Thursday morning, February 8th, Minister of Human Development, Families and Indigenous People’s Affairs, Hon. Dolores Balderamos-Garcia, vowed to go to the people in as many villages as she can, as was requested by the Toledo area representative, Minister of Rural Transformation and Local Government Hon. Oscar Requeña. She said the ministry’s public consultations will continue in Big Falls on Sunday, February 11th.

Minister Balderamos-Garcia attempted to calm troubled waters after the Toledo Maya leaders and Alcaldes ignored the government’s invitation to a consultation in Punta Gorda Town on Saturday, January 27th. Instead, they had assembled en masse in Santa Elena Village, demanding that the government representatives come to them. The ministry officials had avoided Santa Elena for fear that there would have been more confrontation than consultation.

The government has a historical imperative to right the past wrongs that the Toledo indigenous peoples have suffered, Senior Counsel Andrew Marshalleck acknowledged. The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) handed down its “Free and Prior Informed Consent” (FPIC) ruling, which recognized the Toledo Maya’s right to tenure of their traditional lands on April 22, 2015, but the process of giving them their right has dragged on for almost nine years, Marshalleck lamented. This has increased the urgency to set things right within ten years of the CCJ ruling.

It’s no easy process, he admitted, as the Toledo Maya area is primarily rural people who work during the week, so the only time the ministry official may meet with them is on weekends. Holding two weekly meetings in different villages on Saturday and Sunday will take 20 weeks to consult all 41 villages. It’s also costing the government a pretty penny, Chief Executive Officer Adele Catzim declared, over $900,000. Chief Executive Officer Marconi Leal Jr explained that the budget is $200,000 for this fiscal year alone.

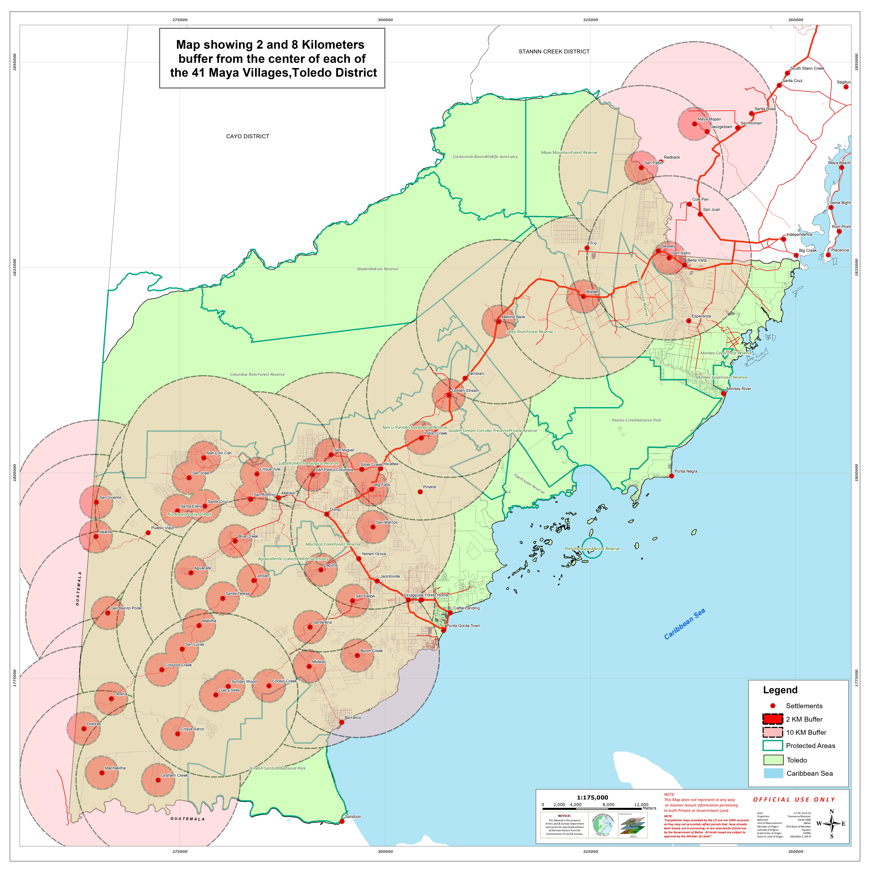

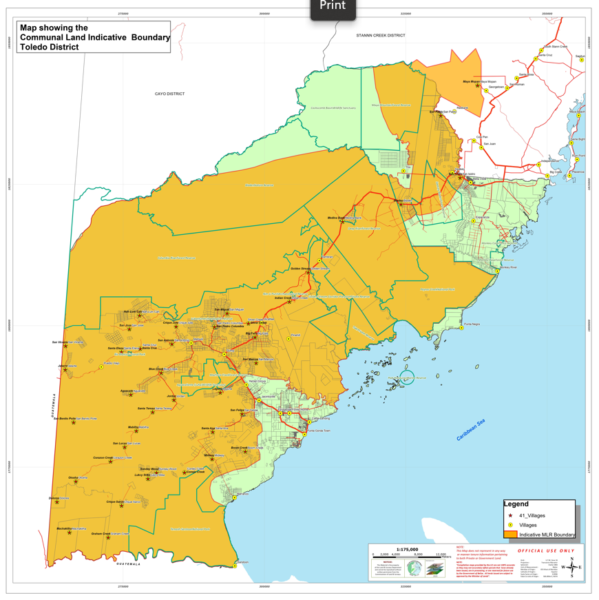

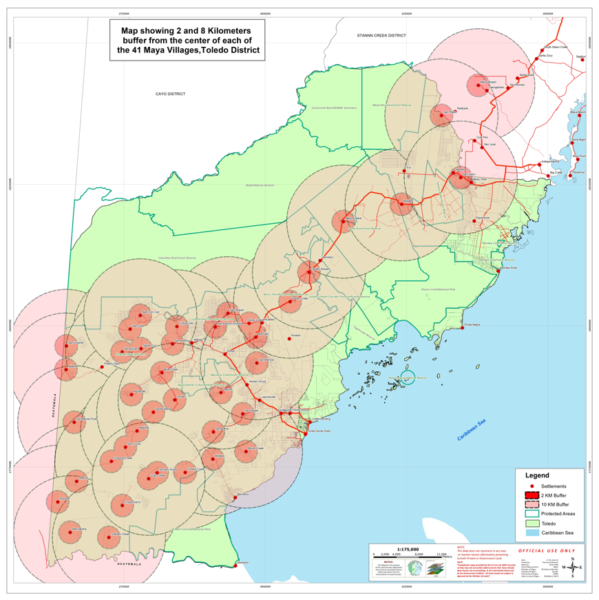

The draft policy defines the traditional communal land for each village to be a series of circular areas measured from each village’s center, with the circle’s radius depending on the number of residents. Thus, villages of less than 500 residents would have the right to communal land tenure of a circle 2 kilometers in diameter, encompassing 315.159 hectares or 776.28 acres. Villages with 500 to 1,000 residents could have communal land tenure of four kilometers in diameter, enclosing an area of 1,256.6 hectares or 6,986.6 acres. A community of over 1,000 villagers would have communal land tenure to a circle 6 kilometers in diameter, an area of 2,827.4 hectares or 6,986.36 acres.

However, no individual can use this communal land as collateral for a bank loan. To allow these villagers access to modern financing, the policy proposes that individual villagers have legal title to the farmland each person is working on if he can prove to have occupied it for 30 years. These individual land titles would be comparable to legal titles issued in any other part of the country. This would give the owner access to modern banking to develop his land.

When the legislation is passed, each of the 41 villages will have seven years to apply for communal land tenure. At least 75 percent of the village residents must approve the application for communal tenure at a meeting to be held within 12 months of the date of application. Those villages that do not wish to have communally held lands do not have to apply if they don’t want to. The policy also allows the state to acquire part of communal lands for a public purpose, at which all fees and taxes paid to purchase title would be reimbursed to the village.

The map of the Toledo district shows where many of these 2km and 3km circles would overlap with neighboring villages. There is no simple mathematical formula to decide who owns what. Marshalleck said the boundaries of communal lands between these villages would look like a jigsaw puzzle when the boundaries are defined. This will require months of consultations with the villagers of such adjacent communities.

Even before this policy was proposed, the ministry had to sort out boundary disputes between neighboring villages, which had expanded until development in one community was encroaching on another. Thus, the former Commissioner of Indigenous Affairs Gregory Ch’oc and Minister Balderamos-Garcia had to deal with many such neighborly disputes. In San Felipe Village, the people had regarded a stream as the natural geographical boundary between them and Laguna Village, which made them feel that the Laguna Villagers were trespassing on their land. Similar disputes exist between Yemeri Grove and Jacintoville and Otoxha and Corazon Creek.

Submitted by William Ysaguirre